Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Industries

Rice farming

Rice paddies were established on the Noto Peninsula around the beginning of the middle era of the Yayoi Period (around 100 years B.C.). Rice cultivation was prevalent in marshlands where there was a good water supply, such as the Ouchi Lagoon in the Hakui City and Nakanoto Town areas. With a warm climate, high rainfall and a plentiful water supply, plus the fact that in winter the ground was covered with snow and production of other crops was difficult, in the Edo Period, rice farming constituted more than 80% of all agricultural crops.

In Noto, the connection with nature and with Shinto and Buddhist Gods, as well as agricultural rituals and local community administration, were all based around the yearly rhythm of rice farming. The terraced rice fields typical of Shiroyone Senmaida in Wajima City, and the numerous reservoirs scattered around Noto Peninsula are evidence of the wisdom of the settlers of Noto to secure land and water systems; and ‘Aenokoto’ (the harvest ritual practiced all over Noto in which the deity of the rice field is shown hospitality) is a festival unique to Noto not seen in other regions.

In Noto, where flat land was scarce, hilly areas often came right down to the coast, and agricultural plots were small, it was common for small-scale farmers to base their livelihood around agriculture so they had a half-agriculture half-fishing lifestyle or a lifestyle that was half-agriculture combined with another regular job in the fishing industry or in forestry, or as a sake brewer or tile maker. Furthermore, it is thought that along with the constraints of the peninsula landscape, unique cultural and lifestyle practices centered in particular on rice farming have been faithfully handed down generation after generation.

Noto Vegetables

In recent years, the ‘satoyama’ sustainable production system has received rich praise from international quarters, such as in October 2010, at the 10th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP10) held in Nagoya City (Aichi Prefecture), when one of the resolutions adopted was to promote the Satoyama Initiative, and in 2011, when the United Nations FAO designated Noto’s Satoyama and Satoumi as Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. The Satoyama system has also attracted great interest from producers and consumers alike.

However, in order to preserve and maintain the satoyama system, people must be involved, and the economic value of the resources of satoyama systems is constantly being questioned. Consequently, a huge influence on the preservation and maintenance of the satoyama system is the ups and downs of the agricultural industry such as rice and vegetable farming (field cropping) in satoyama systems.

After the war, agriculture modernized rapidly in Noto, however traditional agricultural industries and methods, as well as rural cultural practices, biodiversity and rural landscapes were successfully maintained and preserved as an integrated system. In the present day, this is actually a powerful tool in contributing to the increase in added-value agricultural products, an increase in visitors and the rejuvenation of agricultural industries and rural areas in the region.

Furthermore, along with traditions such as festivals and Buddhist/Shinto rituals, there are numerous cooking traditions which have been passed down through the generations and that are still alive today. Behind the cuisine and traditional tastes is the variety of traditional vegetables grown for home-use, and to continue growing these traditional vegetables without losing any varieties is in fact very important for continuing the substantial, unique food culture of the Noto area.

Photo: Cuisine for treating guests during a festival

Diverse environments and diverse fish species

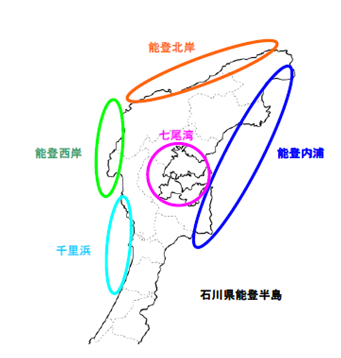

The Noto Peninsula possesses a long coastline, with the geography and environment varying widely. The sea surrounding the Noto area can be roughly divided into 5 big areas. They are Nanao Bay, a semi-enclosed body of water, the Noto Uchiura area facing Toyama Bay and including ria areas (drowned river valleys), the Northern Noto Coastal area facing the Japan Sea, the Western Noto Coastal area with its rocky shores which used to see many northern-bound ships (Kitamae) and foreign ships, and the Chirihama Coastal area with its long sandy coast. The people of the Noto area have therefore adapted to this widely varying coastline and its geography and environment with a diverse fishing industry.

Northern Noto Coast

Western Noto Coast

Chirihama Coast

Nanao Bay

Noto Uchiura

Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture

Figure: The sea of the Noto Peninsula divided into 5 zones

Notes: (1) Proposed by Mr Sakai from the Noto Marine Center

(2) Map - http://www.freemap.jp/

Use of seaweed beds and seaweed

There are approximately 9,000 types of seaweed in the world, and of them, an estimated 1,500 types grow in Japan. It is said that Ishikawa Prefecture has over 200 types of seaweed, and of them, approximately 30 types are used for food in the Noto area (mainly Suzu City and Wajima City).

It is typical for seaweed beds on the Japan Sea side to have a variety of seaweed types growing in the tidal zone (the area between the high water line and the low water line). On the Pacific Ocean side, where the tidal range can be up to 2 meters, the seaweed growing in the tidal zone tends to be distributed in defined bands similar to geological layers. On the Japan Sea side however, where the tidal range is small at less than half a meter, and the coast is not generally shallow, the tidal zone is small. As a result, the seaweed beds are a mosaic of seaweeds, as mentioned above. But while defined distribution is not seen much on the Japan Sea side, a range of seaweed types grow depending on the season and so one of the features of seaweed beds in Noto is the seasonal difference.

Types of seaweed on the Pacific Ocean side are commonly arame, kajime seaweed and kelp, however in Ishikawa Prefecture, it is typical to see sargassum beds (mainly gulfweed), and in winter gulfweed can be seen floating on the surface of the water.

There have been few systematic surveys into the distribution and assessment of seaweed beds in the Noto area, with the exception of the Environment Agency Nature Conservation Bureau’s survey (now known as the Ministry of the Environment Nature Conservation Bureau) of March 1994 – ‘the 4th National Survey on the Natural Environment’. According to the results of this survey, Ishikawa Prefecture’s seaweed beds ‘can be classified into three groups – the gulfweed beds from Kaga City to Cape Rokko at the tip of Noto Peninsula, the gulfweed beds along the rocky shores from Cape Rokugo to Toyama Bay and in the Sotoura area where arame is typical, and the seagrass beds in the silty areas of the same coastal zone’. The length of the gulfweed plants on the Sotoura side is short due to the relatively rough conditions, however those in the Uchiura side where the waves are calmer, grow to a length of 4-5 meters.

Photo: Seaweed beds

i. This paragraph was written based on the article the author researched and wrote for inclusion in the Hokkoku General Research Institute’s ‘Ishikawa Satoumi Survey Report’ (unfinished manuscript) with some major revisions and additions.

ii. The seaweed beds are distributed in the tidal zone and the deeper bathyal zone.

iii. From the Ministry of the Environment Nature Conservation Bureau / Marine Parks Center of Japan – 4th National Survey on the Natural Environment – Report of the Marine Biotic Environment Survey, Part 2 – Seaweed Beds, March 1994, 14. Ishikawa Prefecture, (1) – 1

Reservoirs

In rice cultivation in Japan, management of irrigation is an extremely important job – a technique that governs the harvest amount and the quality of the rice. The Noto Peninsula is surrounded by the sea on three sides, with few areas of flat land and many hilly and mountainous areas. Furthermore, since these hilly and mountainous areas continue right down to the sea, the rivers are short and flow volumes low. Furthermore, rural areas are scattered over the landscape so that large scale irrigation facilities were rarely established.

Since ancient times, reservoirs have been used in Noto as water sources to be used for irrigation. In other regions, during the upgrades of agricultural infrastructure after the war, reservoirs were generally converted to more efficient irrigation facilities, but in Noto, there are still 2,054 reservoirs remaining today. Furthermore, there are also a number of reservoirs that are aesthetically beautiful, such as those that were designated in ‘Japan’s 100 best reservoirs’ (as selected by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan in 2010) – Urushizawa Pond (Nanao City), and Geese Pond, constructed in the Edo Period and the biggest in Okunoto (Suzu City), among others.

The water in reservoirs can be used by all, however they are managed through community cooperation to prevent depletion and they also contribute to creating a cooperative system within villages. Even today, there are organizations at the village level (land improvement districts or irrigation associations) that manage the facilities and the distribution of water. Furthermore, these village level organizations also provide support for the Kiriko Festival (mentioned earlier) and the seasonal movement of laborers (see below), meaning that they play a part in Noto’s cultural services.

The management of reservoir water distribution has a big impact on biodiversity. The reservoir water accumulated over the winter period decreases at the start of Spring in the rice planting period with high irrigation use, but the water level recovers during the rainy season. After the water is used in the summer to autumn period, the reservoirs are drained in the winter period. In this way, since the water level of the reservoirs varies over the year, an ecosystem develops in which emergent plants, fish species and insects are able to adapt to the varying water level.

Reservoirs do not simply exist for the purpose of agricultural water management, but play a part in contributing to a range of services such as the area’s biodiversity and cultural services. However Noto is currently dealing with its biggest problems yet – the difficulty of reservoir management due to a decrease in village populations and workers engaged in the agricultural, forestry and fishing industries, along with the aging population. Crop acreage for agricultural production is decreasing, so that reservoirs are abandoned and a transition is being seen from ponds to wetlands meaning that the local ecosystem is transformed resulting in a threat to biodiversity. A gradual loss of culture and traditions that were previously maintained by villages is now being experienced.

Irrigation Channels

New field development refers to the reclamation of hill areas and lakes to establish agricultural fields. It is said that in Japan as a whole, over a period of about 100 years from the start of the Edo Period, fields increased by nearly double. The Kaga Clan also, who ruled over Noto, encouraged new field development from 1627 onwards, and thus achieved an increase in the production of rice and agricultural crops. The rate of increase of new development production in Noto was 22% in 1684 and 28.9% in 1711.

Noto’s geography is complex, with various landscapes such as mountainous areas, rivers and coastlines, and with a variety of irrigation environments, there were typically many places that experienced water shortages. The farmers of Noto overcame difficult geographical conditions to secure irrigation, and they constructed irrigation facilities such as irrigation channels and reservoirs often in opposition to the power of nature, which they have continued to utilize for over 300 years.

In Wajima City’s Konosu District, the Kasuga Water Channel was constructed with an intake from the Tsukada River to carry water to the Inabune Plains. In the former Funao Village, Tazuruhama Town (now part of Nanao City) a 700m long irrigation canal was constructed along with new field development, and below Takano Mountain in the central area, an underground water channel called ‘Manpo’ was constructed. Furthermore, in the former Fukami Village (now part of Nanao City), there is a large underground water channel called ‘Fukamimura Manpo’ which is 300m in length.

Photo: Funao River Manpo

(Funao-cho, Nanao City)

Agriculture relies on irrigation, so the farmers of Noto were determined to obtain water for this purpose. In times of drought, there were occasionally disputes over irrigation channels, between people of neighboring villages who obtained water from the same irrigation channels.

In Wajima City’s Konosu District, the Kasuga Water Channel was constructed with an intake from Tsukada River, but in Ono Village at the foot of the channel and Furegawa Village which shared the upstream flow, water disputes were constant (see below). At the time, when a drought set in, water distribution would stop for just half a day out of three, and the practice of letting the water flow through was kept, but between 1764 and 1772, people ignored the practice and began to use the water as they pleased. The dissatisfaction of the people of Ono Village continued, and 130 years later, in 1894, they took legal action.

Furthermore, the Oyama Water Channel which flowed through Uchikoshi Town in Wajima City sourced water from the forests with water reservoirs on Hinokuchi Mountain, and the disputes between Soryo Town who wanted to fell the trees, and Uchikoshi Town & Akasaki Town who wanted to protect the Oyama Water Channel (which was their source of water from the forest), continued from 1742 to the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

Behind the increase in agricultural production in Noto were the long disputes between people from neighboring villages over water channels, but the management of water channels gave momentum to the powerful local communities who held the fate of everyone in their hands. In Soryo Town in Wajima City, a lot of money and effort was spent in constructing the Oe Water Channel, but relatively strict water distribution policies were applied. There were various penalties for those who did not abide by the distribution policies, and it is said to have been the catalyst for self-government by the local community.

In addition, irrigation channels played a role in connecting the reservoirs with the rice paddies where amphibian species, fish and insects made their homes. They formed a network with these water sources, providing an environment for the diverse range of living creatures to live and grow, thus contributing to biodiversity.